If there’s something off here, it’s probably because I wrote it in broken stints. - dreamist

During my first time at DEFCON I got to play in one of the several CTFs. Not knowing that Warlock Gamez CTF could facilitate the participation of remote team members, I went into OpenCTF largely alone, and occasionally with the additional help of my coworker (who left his laptop at home. 😛).

Itanic was one of the very few pwnable challenges available for most of the time the competition ran, and the challenge I struggled with the most, only to fail solving in time. So this will serve as both a “what I did” as well as a “what I learned to do better next time”.

There’s additional benefit too in understanding what I missed since now

soen has released his OpenCTF binaries’

sources on Github.

Tools used:

Preface

There’s a familiarity with calling conventions assumed in this blog post, however this may be just a fine time as any other to explain. Compiled C programs tend to follow a consistent scheme for how functions in assembly should receive parameters and be called.

Typically on Linux, 64-bit x86 programs will follow the

System V AMD64 ABI.

What this means is that the first six integer arguments to a function are passed into a function

using registers RDI, RSI, RDX, RCX, R8, and R9, in that order, before

additional arguments are pushed onto the stack. This is how you identify what the arguments

are passed into a called function, and I use this understanding later

to match a function call in x86_64 disassembly to its arguments in source code.

Itanic

The challenge came in a tar file, with the following readme.txt.

Sink the Itanic

A: This is hard B: LostKng.enc is not part of the Challenge, it’s just a fun game included if you get frustrated. -soen

A was right, and B I completely forgot about before long. But I never got frustrated

in a way that I wasn’t still willing to go back to some easier challenge for a while.

The entirety of the TAR file’s contents were:

- itanic: binary to reverse/pwn

-

hello_world.enc: An encrypted binary file? More on this later. quine.encprinter.encdock.encLostKng.enc

Running the itanic binary presents us with:

[ Itanic v 1.005003 ]

Welcome to HMS Operating System

Written on a custom (ish) architecture.

This operating system is perfectly

secure (unhackable like BitFi).

Using the Itanic processor, the superior

processor for the unsinkable HMS

operating system.

Main menu

1. Printer

2. Hello_world

3. Dock

4. Quine

5. Lost Kingdom (not part of challenge, but relaxing and fun!)

6. quit

From here I began to play with the menu options, and crack it open in a disassembler.

Before long I learned that each of these menu items essentially ran

their respective .enc files as arguments to the binary. Ex: itanic hello_world.enc.

Each of these encrypted files began with BOAT\x00\x00\x00\x00, and

could be read in and executed as a program, carrying behaviors

to befit their naming. hello_world for example simply prints hello world.

quine and printer.enc however, print out +s and -s to form brainf–k programs.

If you’ve never seen the Brainf–k language before, it’s a programming language comprised completely of eight special characters, emulating a machine with one byte pointer referencing memory and a program counter. The program counter can land on any of the eight instructions, and perform the appropriate action before moving forward:

-

>: Increments the pointer by 1. -

<: Decrements the pointer by 1. -

+: Increments the value beneath the pointer by 1. -

-: Decrements the value beneath the pointer by 1. -

.: Prints the character represented by the byte beneath the pointer. -

,: Reads in a byte, storing the value beneath the pointer. -

[: If the pointer dereferences to 0, jump to the next]. -

]: If the pointer dereferences to a non-zero value, jump to the matching[instruction.

I had been personally made somewhat familiar with it by solving brain f--k on

Pwnable.kr the week before I left for Las Vegas.

I imagined before long if I could get my own Brainf–k code to run in a similar fashion,

exploitation should be as straightforward as moving the data pointer to leak/overwrite a function pointer.

quine.enc thus prints itself, and printer.enc prints out Brainf–k instructions to print the input it receives.

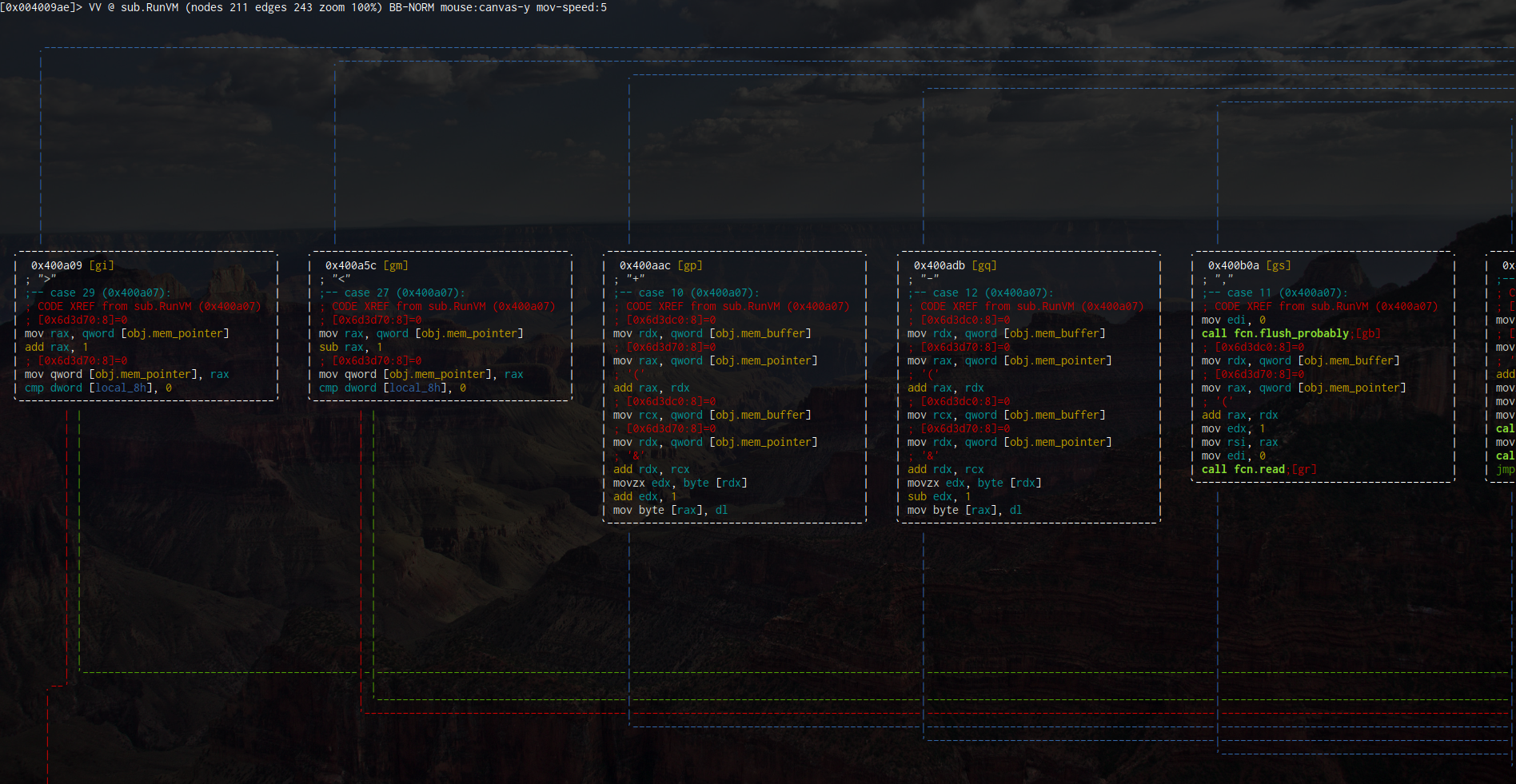

Further looking into the main function reveals that after reading

in the encrypted program and loading it, this program is ran in a form of Brainf–k VM

in the function at 0x4009ae. Here a huge switch case is present that implements all of the

Brainf–k language, in addition to a few unique instructions to the programs it runs.

Attaching a debugger confirms that these programs carry encrypted Brainf–k-superset

payloads, and point us in the direction of reverse engineering the program loader

and binary format.

This much already took quite some time for me personally to reverse in between working on other challenges, and it definitely only seems somewhat straightforward to me now in hindsight.

Loading BOAT files with Dock.enc and New Instructions

I individually made sense of each of the given Brainf–k programs. Since one of these would have to be my initial entryway into gaining control of the data pointer or of the VM.

I found that since the vulnerability couldn’t have been in hello_world.enc,

printer.enc, or quine.enc, the opening must’ve lied within dock.enc.

And so running ./itanic dock.enc gives this prompt:

[ Itanic v 1.005003 ]

[ Your sextant is accurate! ]

[ Casting off the anchor ]

Enter Dock Number:

Setting a breakpoint on 0x400ea3 and reading the string pointed to by 0x006d3dc0 can reveal

the underlying program.

gef➤ x/a 0x006d3dc0

0x6d3dc0: 0x7ffff7bf9010

And immediately it’s apparent that it’s not Brainf–k, but uses some of the additional instructions implemented

in the virtual machine. During competition, I only saw that uses of ? and # stored quad words

in some variables and nulled their original storage locations in the memory buffer,

and * triggered a decryption routine that revealed the actual Brainf–k

we care about. After hitting the breakpoint a few times, the rest of the program should be revealed.

gef➤ x/s 0x7ffff7bf9022

0x7ffff7bf9022: "*>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<++++++.[-]>++++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<++++.[-]>+++[<++++++++++>-]<++.[-]>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<+.[-]>+++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++.[-]>++++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++.[-]>+++[<++++++++++>-]<++.[-]>+++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++.[-]>++++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++.[-]>+++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++.[-]>++++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+.[-]>", '+' <repeats 11 times>, "[<++++++++++>-]<++++.[-]>+++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++.[-]>+++[<++++++++++>-]<++.[-]>>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++>>>+++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++>>>+++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++>>>+++++++[<++++++++++>-]<>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++>>>++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++>>>++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++>>>++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++>>>+++++++[<++++++++++>-]<+++++++>>>++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++>>++++++++++>>+>>+[<[>>+>+<<<-]>>>[<<<+>>>-]<+>", '+' <repeats 16 times>, ">>+<<<[>>+<<-]>>[>-]>[><<<<+>[-]>>->]<+<<[>-[>-]>[><<<<+>[-]+>>->]<+<<-]>[-]>-<<<[>,[>+>+<<-]>>[<<+>>-]<<<<<[>>>>>>+>+<<<<<<<-]>>>>>>>[<<<<<<<+>>>>>>>-]<[", '<' <repeats 40 times>, "+", '>' <repeats 40 times>, "-]", '<' <repeats 42 times>, ">>[[>>]+[<<]>>-]+[>>]<[<[<<]>+<", '>' <repeats 41 times>, "+", '<' <repeats 41 times>, ">>[>>]<-]<[<<]>[>[>>]<+<[<<]>-]>[>>]<<[-<<]", '>' <repeats 40 times>, "[->-<]+>[<->[-]]<[>+<[-]]+>[<->-]+<[>><<<<<<<[-]>>>>>>>[<<<<<<<+>>>>>>>-]<-<[-]]>[-]<<<<<[>>>>+>+<<<<<-]>>>>>[<<<<<+>>>>>-]+[<+>-]<<<<<[-]>>>>[<<<<+>>>>-]<[-]<[-]<+>]<-]<[-],<[>>+>+<<<-]>>>[<<<+>>>-]+<[->-<]+>[<->[-]]+<[>>>++++++++[<++++++++++>-]<++++++++.![-]<-<[-]]>[-]\n"

This program can now be dumped to memory with GDB’s dump function.

dump binary memory dock.bf 0x7ffff7bf9022 0x7ffff7bf97b9

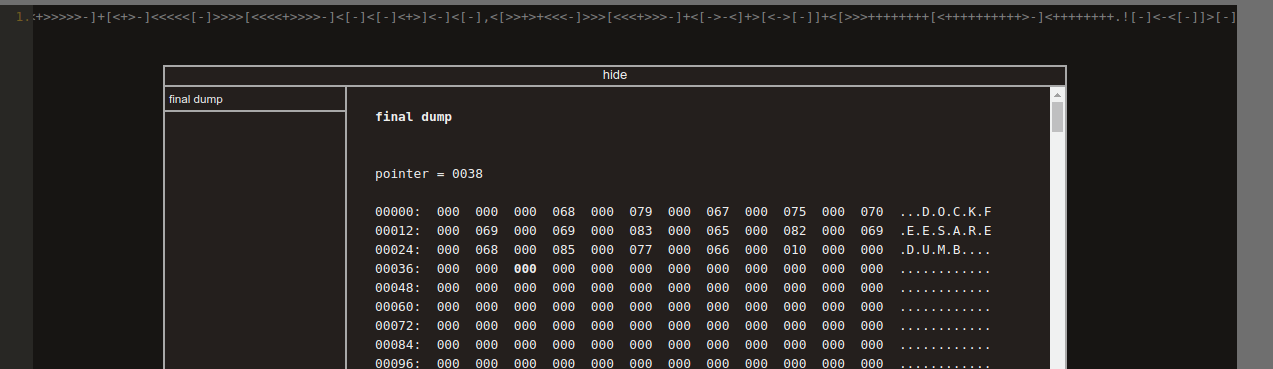

Once dumped, the program can be understood in two parts. The first prints out the prompt for a dock number, while the second reads in the input to match against a secret password. I found it convenient to determine the password by running the second part of the program in a Brainf–k visualizer.

Entering this password and supplying an additional newline gives us access to the program loader! And so continuing the effort of reversing the program loader was an absolute must to move forward.

Some Frustration

What made my frustration escalate at this point was that a new version of the binary was released

just as began to make some progress on understanding the loader.

The older version of the binary dynamically linked

glibc and made identifying libc functions easy,

but the new version had statically linked glibc functions

and thus doubled the work I had to do in function identification wherever I couldn’t

quickly port over the old symbols I marked.

Function identification was perhaps my biggest initial barrier in working through the binary file format reversing.

It’s only in doing this writeup now that I realized I ported some symbols incorrectly, and misidentified

memcpyasmemset, adding a great deal of confusion to my reversing efforts.

Failing to Reverse the File Format

The function @0x401282 I had renamed to sub.LoadProgram.

This function is passed a pointer to the encrypted binary file read into memory.

From reading it’s disassembly, it became clear that it cleared 0x3c bytes

of space on the stack, and then loaded a quad word (8 bytes in length) from

a 0x50 byte offset into the loaded binary file to pass into malloc as a

size argument. I didn’t mark this down, but this should indicate that this member

is some form of size.

binary_format_struct {

...

0x50: uint64_t size

}

Beyond this, the first two functions called were obviously involved in some kind of encryption, but I couldn’t identify the encryption scheme used, or what I could do besides setting a breakpoint after to get some additional information on it.

Encryption

The first encryption-related function took as an argument a pointer to

data at a 0x20 offset within the read binary file.

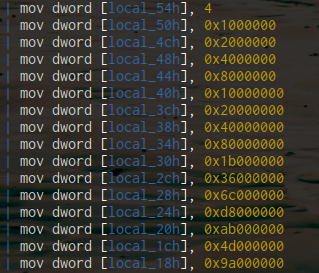

This function has two main loops performing some math that was and perhaps would still be beyond me,

using a long list of large constants on the stack.

The second encryption-related function contains loops using two additional math functions I didn’t find fruitful to reverse. And this is where I attempted to shamefully ask the organizers for my first hint of the event, to which there may have been miscommunication. I had heard the author explain that the encryption was custom, but this wasn’t so.

The large constants on the stack in the first function happened to be a useful hint

for Googling. Shortly after the CTF ended I found from an archived textbook that these constants

were used in AES for key scheduling.

Looking for AES implementations on Github then, I found

one written by Brad Conte

that seemed to have all of the contants in a function that matched up very well

to the first encryption function, aes_key_setup. It turns out that this was the exact

source copied for implementing the encryption in the Itanic challenge.

In repeating the same searches on Google now, maybe it’s my use of a VPN from my desktop, but I wasn’t able to find neither the textbook nor the tiny-AES-c implementation as Google results. I still feel rather convinced however that if I could have identified the sources used in this manner I’d have been able to at least identify that the encryption was AES.

Looking into itanic’s source,

I can see now that the following function was aes_decrypt_cbc.

And I’m not sure I could’ve identified CBC mode in the end anyhow. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

I simply need to study crypto more.

From this point I’ll be relying on the sources to walk through the rest of the challenge.

From the setup to the aes_key_setup call, I see that at a 0x20 offset

into the binary is a key parameter.

binary_format_struct {

...

0x20: char key[]

...

0x50: uint64_t size

}

Then, aes_decrypt_cbc is called with data beyond a 0x58 offset into the binary file

serving as input. The data at a 0x40 serves as an IV.

The decrypted output is stored in a large allocation made equal to the previously

determined size, and would turn out to be the encrypted Brainf–k code.

binary_format_struct {

...

0x20: char key[]

0x40: char iv[]

0x50: uint64_t size

0x58: char encrypted_code[]

}

Hashing

During competition I wasn’t sure how to identify the last three math-related functions

in what I called sub.LoadProgram, but sources indicate that these are:

SHA256_init(SHA_CTX *c)SHA256_Update(SHA_CTX *c, const void *data, size_t len)SHA256_Final(unsigned char *md, SHA_CTX *c)

In that order, I can understand that following the decryption, these functions are used to gather the SHA256 hash of the decrypted code, and determine if it matches the first 0x20 bytes of the binary file.

binary_format_struct {

0x0: char hash[0x20]

0x20: char key[]

0x40: char iv[]

0x50: uint64_t size

0x58: char encrypted_code[]

}

This matches the CodeBlob struct that apparently represents the binary file following the magic quad word.

Following this, I expect that exploitation would follow in typical Brainf–k interpreter fashion. If I write about the similarly named challenge on pwnable.kr, maybe then I can explain the straightforwardness of having an arbitrary relative read/write primitive.

Epilogue

This was about as far as I’ve continued to work on the challenge beyond OpenCTF’s end.

During the competition, for all of the hours I put into this challenge, I could’ve given more time to some other challenges that would’ve kept us higher up on the scoreboard as the end of the competition neared. The intro warned that it was hard, but I simply took that as a challenge, and I must admit that the gap in my personal crypto skillset made it a bit much for me after all.

I’d love to actually finish writing an exploit for this binary with my new understanding, or even a decent unpacker for the binary format, but that will likely not be anytime soon. If I do, there’ll be a part 2.